Making Your Business More Socially Responsible

We wrote this guide for people working within organizations that want to make their employer more socially responsible. While this guide was originally meant for people in corporations, we have found that the lessons here are applicable to all. Big or small. Publicly traded or privately held. Governmental, NGO, Startup, or International conglomerate. If your organization employs people, this guide will help you understand what your organization can do to minimize your environmental footprint, mitigate unintended negative consequences, and ensure your operations are creating a positive impact to society and the world.

This guide is seperated into the following Sections

SECTION I: History & Definition of CSR

- Chapter 1: History of Corporate Social Responsibility

- Chapter 2: What is Corporate Social Responsibility

SECTION II: The Business Case for CSR

- Chapter 3: What is the Future of CSR?

- Chapter 4: Why Your Business Should be Socially Responsible

- Chapter 5: Why the World needs you to Step Up

SECTION III: How to Launch a CSR Program at Your Company

- Chapter 6: Getting Started at Your Company

- Chapter 7: Develop a Strategy

- Chapter 8: Look for Bright Spots to Build Momentum

- Chapter 9: Launch a Pilot

- Chapter 10: Report on Impact and Set the Stage for Long-Term Measurement

SECTION IV: Scaling Your CSR Programs

- Chapter 11: Scale with Partnerships

- Chapter 12: Winning over Executives

- Chapter 13: Empowering (and Aligning) Employees

- Chapter 14: Going Public Within the Company and Beyond

- Chapter 15: Continue to Scale

SECTION V: Appendix & Resources

Why this guide?

Simply put, the world needs you. Capitalism is one of the world’s most powerful systems, and it is one that must also evolve.

Your organization, big or small, is part of it. You too must evolve. This guide will help you take meaningful, long-term action that can help create a sustainable planet free from injustices and inequalities.

As Paul Polman, former CEO of Unilever shares

The cost of inaction is higher than the cost of action

We must do more, faster

Jonathen Franzen, in the article What if we Stopped Pretending? says it best:

A false hope of salvation can be actively harmful. By voting for green candidates, riding a bicycle to work, avoiding air travel, you might feel that you’ve done everything you can for the only thing worth doing. Whereas, if you accept the reality that the planet will soon overheat to the point of threatening civilization, there’s a whole lot more you should be doing. In times of increasing chaos, people seek protection in tribalism and armed force, rather than in the role of law, and our best defense against this kind of dystopia is to main functioning democracies, functioning legal systems, functioning communities. In this respect, any movement towards a more just and civil society can now be considered a meaningful climate action... To survive rising temperatures, every system, whether of the natural world or of the human world, will need to be as strong and healthy as we can make it.

The frameworks presented in this guide are applicable to everyone, regardless of your stage in the social impact journey. While geared towards for-profit businesses, people within nonprofits and governmental organizations can also benefit from the guidance offered here. If you’re excited about this work, we cover these concepts in greater depth in our MovingWorlds Institute.

Chapter 1: History of Corporate Social Responsibility

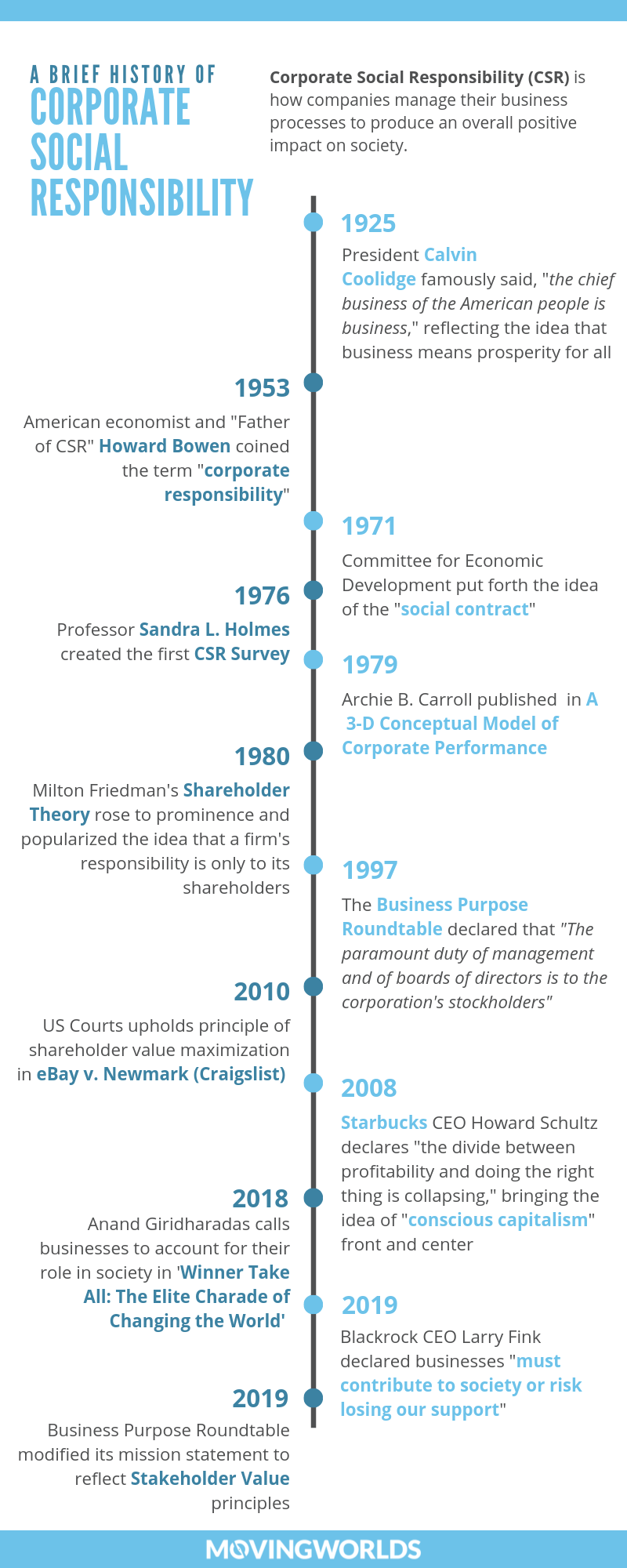

To understand the current state of Corporate Social Responsibility (often times called CR or CSR), it’s useful to look at the history of Corporate Social Responsibility. While corporations have been around since the Dutch East Indies Trading Company incorporated in 1602, their rapid rise in the 1790’s in America and Western Europe brought corporations into global prominence. By this time, issues between workers and the wealthy owners of corporations were commonplace (the first strike in America was in 1768), but it was the rise of unions through the industrial revolution in the mid 1800’s that enabled workers to leverage collective bargaining for safer, more secure, and more equal jobs. The growth of both companies and unions led governments to ultimately get involved to help define the role of corporations in society, a debate that is still very much alive.

In 1925, American President Calvin Coolidge famously said, “The chief business of the American people is business,” reflecting the broader notion that if the USA grew businesses, it would create prosperity for all. The proliferation of different legal entities (i.e. C-Corporations, Limited Liability Corporations, Partnerships, Limited Liability Partnerships, etc.) throughout the 20th century enabled more types of business to rise and prosper, with their investors and leaders given more legal protections. Laborers were weakened during this time to help promote the growth of business, yet as activism increased after World War II and The Great Depression, people became activists against companies, too – sometimes the very ones that employed them.

American economist Howard Bowen invented the term “corporate responsibility” in his 1953 book, Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, and has since become known as the “father of CSR.” A slew of other books quickly followed, including Joseph W. McGuire’s 1963 Business and Society, and Clarence C. Walton’s 1967 Corporate Social Responsibilities. In 1971, the Committee for Economic Development put forth the idea of a “social contract” when it published a three-tiered model of Social Responsibilities of Business Corporations. According to the Association of Corporate Citizenship Professionals: “The social contract is based on the idea that business functions because of public ‘consent,’ therefore business has an obligation to constructively serve the needs of society. This is often referred to today as ‘license to operate’ – that is to contribute more to society than solely their products for sale.” In 1976, professor Sandra L. Holmes created the first CSR survey, and shared results in a report, Executive Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility. In 1979, Archie B. Carroll, in his work A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance, summarized that that companies (1) adopted principles, (2) created formal processes to achieve principles, and (3) developed policies to align the company. With these books, the idea of CSR was introduced to the public consciousness.

On the other hand, Milton Friedman’s Shareholder Theory, which was first published in the 1970’s and rose to rapid prominence in the 1980’s, stated that a firm’s responsibility is only to its shareholders. Around the same time, Peter Drucker’s Management by Objective principles, which took hold in MBA programs around the world, gave corporate leaders the tools to become profit maximizing machines in the 1990’s and early 2000. To cement their intent, the Business Purpose Roundtable, a convening of the world’s most successful CEO’s signed a declarative statement in 1997 that said, “The paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporation's stockholders”. Indeed, these principles were upheld in US courts in the landmark case eBay v. Newmark (Craigslist) in 2010, where the Court ruled that “Directors cannot . . . defend a business strategy that openly eschews stockholder wealth maximization.” In 2012, Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court Leo Strine, Wake Forest L. Rev wrote, “The object of the corporation is to produce profits for the stockholders and . . . the social beliefs of the managers, no more than their own financial interests, cannot be their end in managing the corporation.”

Workers, citizens, and communities, empowered by online review systems, open forums, and social organizing means, rose against this philosophy of ‘shareholder capitalism’ and forced companies to evolve their thinking to include stakeholders across society. Social critique against companies increased as trust in companies declined, influenced strongly by the massive inequalities between shareholders of large corporations and their employees and competitors. The Edelman Trust Barometer themed its 2019 report “Trust at Work” showing a shift in what matters most for companies to participate in society - they must be trusted. Corporate citizenship has grown in the last couple decades through PR activities in an attempt to rebuild goodwill. Starbucks, an early adopter of highlighting corporate commitment to the world, brought “conscious capitalism” front and center with ideas like “it’s one cup, one planet,” where consumers could make up for their choices that hurt the planet by making coffee purchases that were supposedly doing some environmental good. Philosopher Slavoj Zizek, in his 2009 book, First as Tragedy, Then as Farce (summary video here), berated this idea, sharing that it was akin to demolishing communities with one’s left hand in the morning, only to help rebuild them in the afternoon with their right hand. In his 2018 book, “Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World”, author Anand Giridharadas built on this critique and pummeled businesses, wealthy foundations, and philanthropists saying that the act of “giving back” was not sufficient to mitigate the harms and inequalities created by their core operations. In other words, generating wealth through irresponsible activities could not be redeemed by then giving away a portion of the profits.

Businesses began to notice this tide of resistance. In January of 2019, Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock, one of the world’s largest investment banks, declared that clients must “contribute to society, or risk losing our support.” In 2019, the Business Purpose Roundtable modified a 20-year-old mission statement on the purpose of business, moving away from the outdated idea that businesses only exist to maximize shareholder wealth, and toward a more inclusive idea that, businesses must also exist to benefit their employees, supply chain, and the communities they operate in. The 180 CEO’s that signed this - including those from Amazon, Pepsi, and IBM - realized that they no longer had a choice. According to Deloitte’s 2019 Human Capital Trends Report, this year marks the rise of the “social enterprise”, a business model that combines profit-making with activities that respect and support the environment and its stakeholder network. According to Deloitte, an “Intensifying combination of economic, social, and political issues is forcing HR and business leaders to learn to lead the social enterprise—and reinvent their organizations around a human focus.”

Chapter 2: What is Corporate Social Responsibility

With this in mind, let’s more closely analyze the often-confused definition of “corporate social responsibility” (CR or CSR for short). There is a popular misconception that CSR is just the philanthropic arm of a company, but CSR is so much more than simply mobilizing volunteers and giving away money. Rather, CSR’s aim is to minimize the negative consequences of a business’ operations on the environment, planet, and people, while simultaneously identifying ways that its people, processes, partnerships, products, and profits can be used to help create a sustainable planet free from injustices and inequalities. (We elaborate on this idea of “do more good” vs. “do less harm” in chapter 5).

Mallen Baker defines CSR as, “...how companies manage their business processes to produce an overall positive impact on society. It covers sustainability, social impact and ethics, and done correctly, should be about core business - how companies make their money - not just add-on extras such as philanthropy.” The World Business Council for Sustainable Development states that “Corporate Social Responsibility is the continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as of the local community and society at large”. Many more definitions exist, but the takeaway is that true CSR exists to ensure the business itself is world-positive, not just as a philanthropic add-on.

However, these definitions assume that all companies are at the same maturity level and have the ability to prioritize CSR, which is never the case. For this reason, we think that Deloitte’s framework of “Corporate Social Impact” archetypes is a more realistic way of defining CR. In the report, Driving Corporate Growth Through Social Impact: Four Corporate Archetypes to Maximize Your Social Impact, Deloitte shares that “Social impact has evolved from a pure PR play to an important part of corporate strategy to protect and create value. In our recent study, we identify the four social impact archetypes companies typically fall into:

- Shareholder Maximizer: The primary motivation of the Shareholder Maximizer is short-term shareholder value. Their strategy emphasizes risk mitigation.

- Corporate Contributor: Social impact for the Corporate Contributor is driven by external factors, including key stakeholder relationships. Their strategy is siloed within the firm.

- Impact Integrator: For an Impact Integrator, social impact is integrated within firm strategy and across business units.

- Social Innovator: Social impact is an integral piece of the overall strategy for a Social Innovator. Their business creates socially-conscious goods/services and markets.

These distinctions are important as they more accurately represent the reality of the business landscape we know today. A venture-backed startup will almost always be a shareholder maximizer. A well-established company seeking to build trust with consumers can mobilize its 5 P’s (Profits, People, Processes, Products, and Partnerships) and be a corporate contributor. A privately held company, like Patagonia, can be an impact integrator by funneling its profits and improving its supply chain, and a Benefit Corporation or Cooperative can be a social innovator by creating a market-driven method to create a sustainable solution to a world challenge.

Chapter 3: What is the Future of CSR?

Research we conducted in 2018 and 2019 revealed an overarching trend: corporate social responsibility is becoming integrated into all aspects of a business. In the same way that companies are embracing the use of data to improve every aspect of its operations, we anticipate that all companies, regardless of their archetype, will integrate social & environmental responsibility in every aspect of its business. Just as every employee has a human resource business partner, we see a world where every employee also has a contact that can help them integrate more purpose into their work and make more of an impact with their careers.

Our research led us to develop a scorecard to assess a company's readiness to scale its social impact programs. One of the most important factors is whether different business units are approaching CSR as a means to achieving its core objectives. While companies start with integrating social impact into leadership development & HR programs, many more are following with supply chains, distribution, market development, and more. This trend is certain to continue. And as we wrote about in Fast Company, companies will adopt a human-centered design approach in developing these programs.

Chapter 4: Why Your Business Should be Socially Responsible

There are many research-backed reasons why businesses should be socially responsible, AND evidence that they will financially benefit from doing so. A few of the most commonly referenced and studied benefits are:

- Consumers are demanding corporate responsibility, meaning that engaging in authentic CR will increase your sales (the wrong approach can lead to negative performance).

- People want to work at companies with world-positive missions and products, and companies who integrate CR will recruit and retain better talent.

- Employees deliver more value to businesses when they understand how their work is part of something bigger.

- Companies can foster innovation for new products, processes, and operations by exposing their teams to new markets and creating interactions with users.

- Companies can learn about new markets and gain insights to prosper there by creating opportunities for decision makers to get first-hand experiences in these places.

- Companies can earn new revenue-positive partnerships, especially along supply and distribution chains where there are ample opportunities to build the capacity of these partners.

- Companies can avoid costly legal regulation and lawsuits by prioritizing ethical practices and earning goodwill.

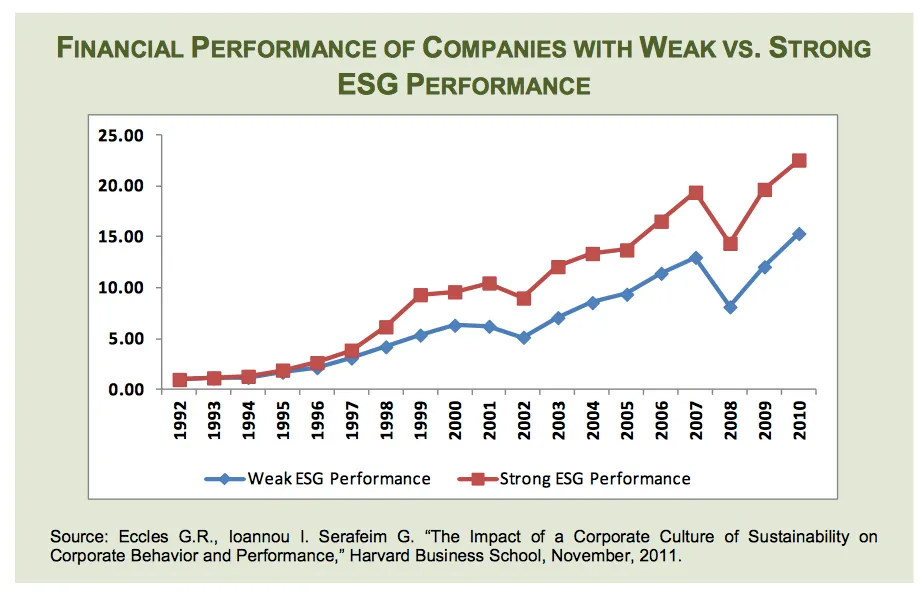

- Companies integrating CR can increase access to capital by creating opportunities to qualify for funds committed to ESG (environmental and social good) (a rapidly growing opportunity).

- It is a moral imperative.

Report after report after report shows that, in the long-term, investing in environmental and social good initiatives will help a company increase its financial performance. Washington State University has a nice infographic further showing the benefits.

Chapter 5: Why the World Needs You to Step Up

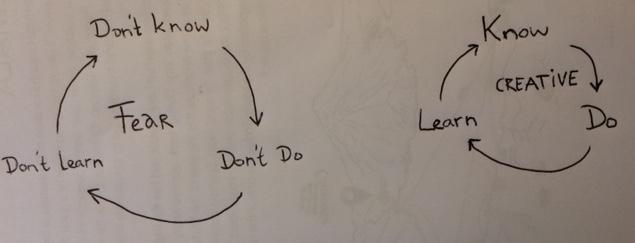

The truth is, even though the case for social responsibility is very clear, many executives still don't invest in it. Some companies try to invest in CSR, but do so with the misaligned intent, which can actually result in negative effects on the business. However, if a business invests in CSR out of authenticity and with good strategy, it can have resounding impact on the company, its employees, and the communities they interact with.

When a well-run business applies its vast resources, expertise, and management talent to problems that it understands and in which it has a stake, it can have a greater impact on social good than any other institution or philanthropic organization. - Michael Porter

Sadly, despite all the talk about social responsibility and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, the world is NOT on track to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals unless more drastic action is taken. Your efforts, however small, are critical to helping shift the global economy in a sustainable, equitable, and just direction.

Chapter 6: Getting Started at your Company

Regardless of your position at your company, we believe that every employee, at every level, can affect positive change and help their company become more socially responsible. There are two main ways to create change at a company, as explained by Anand Giridharadas, author of Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World: (1) Help it do more good, and/or (2) Help it do less harm. Before deciding on WHAT you can do within your company, you first need to understand WHY your company will do something, and then HOW to get started.

As we teach in our MovingWorlds Institute, the first step to creating change is creating a systems map as part of a pragmatic approach to understand where your company can become more world-positive, and then identifying where you have the ability to understand and then influence stakeholders. (Want to learn more about systems mapping? Checking out this great guide from FSG).

Author note: You’ll notice here that this guide does not start with the assumption that you have an idea. In fact, we recommend you leave any preconceived ideas at the door. The hard truth is that most ideas don’t work, and you don’t want to commit career suicide. While there are likely some great insights and creativity behind those ideas, our approach recommends that you put this to the side and start with a structured, easy-to-follow process that will help you generate ideas with a high success rate.

At the most basic level, every company is comprised of People, Products (and/or Services), Processes, Partnerships, and Profits: The 5 P’s. It your job to identify corporate-strategy-aligned ideas that are world-positive.

To get started, For each of these 5 P’s, you’ll want to brainstorm ways your company can do more good (DMG) as well as do less harm (DLH). Here are a few examples of DMG vs. DLH thinking:

- People: DMG by encouraging them to volunteer. DLH by eliminating gender-based pay gap issues.

- Products: DMG with a buy-one-give-one model; DLH by making sure your entire supply chain is traceable and ethical.

- Processes: DMG by effectively distributing clean water with your operational excellence in the event of emergencies. DLH by upskilling your employees so they are not put out of work when you automate their jobs in the pursuit of efficiency.

- Profits: If your company has healthy profits, you can DMG by giving money away. You can also DLH by increasing salaries of your employees to attack income inequality and by paying taxes.

- Partnerships: DMG by donating to a nonprofit that supports the communities you work in; DLH by stopping to price gouge suppliers and distributors.

At this stage, you are likely to encounter the question: What is actually good vs. harmful? Luckily, as of 2015, for the first time in the world, we have a global framework that sets measurable targets for what will help achieve a sustainable, just, and equal world: The 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs create a useful framework to help you make sure that the initiative your company is working on is actually contributing to a more sustainable, just, and equal planet. An easy way to generate DMG and DLH ideas for your company is to use the SDGs as a brainstorming framework: Pick three of the 17 SDGs that your company canres about, and then ask if there is a way your company can do more good AND do less harm for each of the 5P’s of your business (template below). If your company has no history of involvement towards the SDGs, you can either pick a couple that you think are most relevant, or even conduct this excercise for every one of the 17 SDGs.

Not sure how to start? Grab a team member and start brainstorming answers to these questions for each of your 5 Ps:

- DMG: Is there a way we can mobilize our people to do some good to (SDG #1) end poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities? DLH: Are we doing anything with our people that might be creating harm and propagating poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities?

- DMG: Can our products (or services) alleviate poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities? DLH: Is the delivery of our products (or service) propagating issues that lead to poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities?

- DMG: Can our processes alleviate poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities? DLH: Are our operations/processes propagating poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities?

- DMG: Can our profits be used to alleviate poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities? DLH: In the generation of our profits, are we doing things that are propagating poverty we should stop? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities?

- DMG: Can we use our partnerships to help end poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities? DLH: Are our partnerships structured in a way that is propagating poverty? How can we refine this idea to align with our corporate priorities?

Once you get through the 5Ps for SDG #1, then go through the same process for the other SDGs, or simply zero in on the ones your company is already committed to.

Additional guidance on how businesses can support the SDGs was published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Even more specific guidance, by industry, has been published by the United Nations SDG Impact organization.

For a full list of the 17th SDGs, as well as a template to have your brainstorm, use this simple (albeit dense) table:

Download a copy of the template in our 5-step guide to becoming a social intrapreneur.

Download a copy of the template in our 5-step guide to becoming a social intrapreneur.

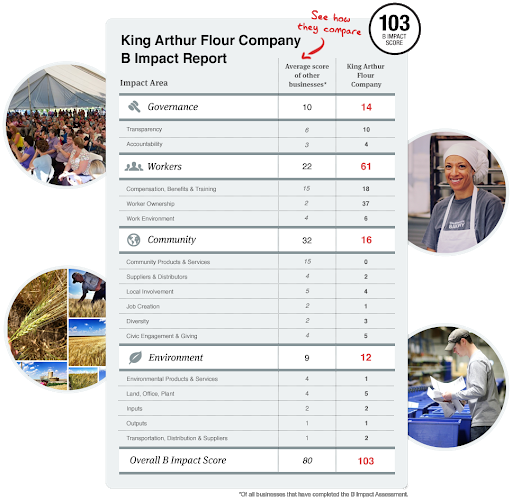

Another task that you should complete during this stage is taking the Benefit Corporation Assessment. While the assessment is meant for organization leaders, anybody can create an account and take the assessment. Regardless of your role, we recommend you act as if you’re the leader of your company and take the assessment to the best of your knowledge. Doing so will not commit you, nor your company, to anything. In the process of taking this assessment, you will see examples across issues like governance, workers, community, and the environment. For each, the assessment will also give you practical guide on how to improve.

If your company leadership seems open, we recommend you try and take the assessment with them and then take steps to quality for Benefit Corporation status.

Chapter 7: Develop a Strategy

Once again, you’ll notice that this guide does not launch into making an idea happen. We actively dissuade this type of thinking, and instead encourage you to create a strategic approach to make an idea happen. You want to make sure you’re falling in love with the problem, not necessarily with your solution. For this, we turn to lessons that we published in Conscious Company:

- Create a Systems Map, and Understand the Drivers & Barriers for Key Players Once you’ve created your systems map and brainstormed ideas, you’ll want to revisit your map and better understand the different people connected to your idea. For each, you’ll want to understand their drivers and barriers.

- Propose a Pilot that Will Actually Work While this sounds obvious, execution here is facilitated by using a human-centered design thinking approach. You’ll want to walk through the five phases of this process to create a viable idea.

- Build the Business Case and Validate Your Hypotheses We recommend using a Business Model Canvas to make clear the assumptions that your idea is resting on, and for guidance on what you need to address first.

- Secure Executive Sponsorship and Promotion Initiatives within companies cannot exist without executive support. In our scaling impact at your company scorecard, the very first thing we analyze is if your company has the needed support to scale up an idea. You’ll want to do something similar to ensure your work won’t get squashed before you get started.

- Navigate the Naysayers We wish we didn’t have to put this in our guide, but we do. New ideas will always face “corporate antibodies”, even world-positive ones. From Day 1, you’ll want to make sure that you’re taking time to understand why your idea might encounter opposition, and taking steps to handle that before it comes back to stall you. Social-impact thought leader Nate Wong explains how to overcome corporate antibodies to intrapreneurship in this episode of #BeyondBuzzwords.

For help with these 5 methods, download our free 5-step workbook.

For additional support, we also recommend you take the Benefit Corporation Assessment. Even if your company is not a B Corp and has no intention, taking the free assessment will give you practical ideas and examples across different aspects of your business: Governance, Workers, Community, Environment, and Customers.

Chapter 8: Look for Bright Spots to Build Momentum

Undoubtedly, people within your company are also working to try and make things better. They might be activists, they might be organizing local events, or they might be currently lobbying their manager, director, HR, or a company executive to do more. You are never alone. There are lots of ways to find other people within your company looking to also create a change. Here are a few ideas on how to find them:

- Start at nodes: Start by finding well-networked people at your company. Who is that person who knows everything that is happening with the business? Who manages the internal announcements for the company and might be getting asked to help promote activities? What is listed on existing content and social media assets? Another good place to look for nodes is to see if there are any current volunteer matching or giving platforms set up for your company. Find the manager of that tool to find more information.

- Work from the top down: Approach senior level people to find colleagues who might already be trying things. Try a very easy ask, like “I’m looking to get involved with any social good activities that might be in place. Can you direct me to anybody that might know of existing initiatives?”

- Work from the bottom up: Scour internal assets. This can include things like: Files (Are there proposals, reports, or other documentation that might exist on shared drives or knowledge bases?), Groups (Virtual of in-person, are there any Employee Resource Groups (ERGs) or Affinity Groups (AGs) (Check out this useful guide from Namely on creating one at your company), slack channels, teams, social networking hubs, email list-serves, or other that might help you find a group of people already working in this area?), and Media (Are there any examples on social media, internal announcements, conferences, or external PR that allude to who may have been active in advancing social good initiatives?)

- Work from the middle out: Talk to managers, HR business partners, Chiefs of Staff, office managers, corproate affair teams, and executive assistants. Ask simple questions, similar to what you might ask a senior leader: “I’m looking to get involved with any social good activities that might be in place. Can you direct me to anybody that might know of existing initiatives?”

If initiatives are already underway, start by helping out existing efforts before trying to push your own agenda. People that have been able to make progress already are immensely valuable as they can help you understand what it takes to get something going at your company. In addition, they may have the needed connections. Help them first, and then include them in the design process mentioned above to make sure you are building alliances, and not competition.

Chapter 9: Launch a Pilot

As LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman said, “If you are not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you've launched too late.”

Regardless of size, support, and buy-in, it’s important to move quickly. Launch a pilot and make sure to document the process. As a recent example, see this story from Airbnb. Still in rapid growth phase, Airbnb did not have an official CSR program. However, when its community tried to open up their doors to help people affected by disasters, Airbnb reacted quickly. The program has continued to evolve, and now actively encourages hosts to participate during any disaster.

Keep a journal of events. Save your workback timeline. Take photos. Have a survey ready to go at the end so you can capture feedback. Once you’re done, personally debrief with all stakeholders so you can learn what you should keep doing, stop doing, and start doing.

Chapter 10: Report on Impact and Set the Stage for Long-Term Measurement

To grow from pilot to program implementation, you’ll need to prove that it’s really making an impact on the intended audiences. In other words, outcomes are more important than inputs (i.e. number of volunteer hours) and outputs (i.e. 1,000 meals served). The real question to answer is how did your company create meaningful outcomes for the people it is attempting to support.

There are definitely wrong and right ways to measure feedback. A useful article in Stanford’s Social Innovation Review shares 10 reasons not to measure impact, and what to measure instead.

Often times, we’ll see people obsess about writing surveys that ask too many questions. However, at the early stages of your program, fewer, more powerful metrics are the key. We recommend identifying two to three key data points (aka Key Performance Indicators - KPIs) for 3 main stakeholders: 1. Company decision makers 2. Employees 3. Organizations you are benefitting. By virtue of having gone through an inclusive design process, you will be able to also pick up on key decision-making criteria that will inform stakeholders decisions about whether to keep investing time and resources. Ask yourself the following questions to help you pinpoint KPIs:

- What metric will company decision makers want to know? Probably something like “Do the managers of employees that participated feel like it was a good use of their team member’s time?”

- What will employees want to know? Probably something like “Would you recommend this experience to a colleague?”

- What will benefiting organizations want to know? Probably something like “This partnership is accelerating our mission in a way we could not do ourselves.”

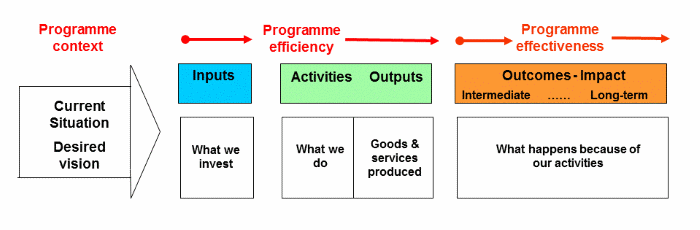

As time goes one, you’ll want to further develop your impact story with a Theory of Change (ToC). This ToC should NOT be perfect. It’s easy to obsess over measurement, but all you really need to do at this time is boil your first measurement down with the goal of continuation and evolution. This means that the data shows all stakeholders why you should keep investing in the program (continuation), and that you capture insights to further improve the program (evolution). The team at Learning for Sustainability has a nice example of a ToC:

The basics in your TOC are as follows, and should be answered for each audience:

- What were the inputs?

- What did each audience do?

- What were the outputs?

- What were the outcomes (short-term to intermediate)?

- What is the impact (long-term)?

We recommend that you do this BEFORE you start to develop hypotheses about your program. Then you’ll want to validate the hypotheses at each stage AFTER you run your pilot through interviews. Once you identify themes in interviews and volume grows, you’ll then want to use more surveys and quantitative research to scale your reporting.

Chapter 11: Scale with Partnerships

Often times, you’ll need to start a partnership with an organization to get to a pilot. However, before going too far in that partnership formalization process and requiring too much structure, you want to make sure this partnership is part of your - and their - scale-up strategy, as partnerships can be costly and time consuming for all parties. As such, we recommend more structured partnership building AFTER you prove your pilot. The first steps should be as lean as possible.

Ideally, during Chapter 5’s “Strategy Development” above, you already took time to work with partners to understand how your company could support their efforts. As your project progresses and you see a path to scale, you’ll want to build partnerships to scale more effectively. In order to do this, we recommend the Network Leadership mindset. Networking Leadership is a framework for partnerships that emerged from studying how some of the most successful and sustainable projects have been able to effectively scale without massive fundraising. The framework is based on four principles and five steps to partnership creation. The four principles are: (1) Trust, not control; (2) Humility not brand; (3) Node not hub; (4) Mission not organization. It’s important to embody these as you go through the 5 stages of building this type of partnership:

- Clarify purpose: A clear agreement between partners about the purpose of the partnership, as well as an agreement to keep evolving it with time and experience.

- Convene the right people: According to Converge, the research body behind this framework, “The ‘right people’: 1) collectively represent all parts of the system, 2) have the ability to get things done, and 3) are willing to cross boundaries and work with people who may have very different perspectives and priorities. This includes everyone impacted by the issue, even people you may not want to work with.”

- Cultivate trust: Partnerships are challenging and people don’t always enjoy each other, but they must trust each other, and proactive steps must be taken to build trust.

- Coordinate actions: Each stakeholder likely will have its own processes and actions, many already in process. These can continue, but efforts must be taken to share actions and learnings. Parties should strive to complement rather than duplicate each other's efforts.

- Collaborate generously: According to Converge, “Assume positive intent, communicate frequently, and consistently look for opportunities to work with others in support of shared goals, not personal gain.”

Chapter 12: Winning over Executives

It’s vital that executives are part of your strategy, and you should involve them throughout your project in each of the design thinking phases. However, remember that executives are unique individuals and may not be swayed for rational reasons. In the telling article 'The Case for CSR is Clear, So Why Don’t More Invest in It?', Sebastian Hafenbraedl and Daniel Waeger explain that,

First, we find that the vast majority of executives already believe in the business case for CSR. There is hence no need to convince them of its existence. And second, our findings indicate that the executives who believe in the business case for CSR are also those who have difficulty seeing the problems CSR initiatives are supposed to solve. And since they cannot see the problems, they will not sponsor CSR-initiatives designed to solve them. Rather than talking to executives about the financial benefits of CSR, advocates would have much more impact by focusing on helping executives to take off their blinders and overcome their ideology, and in that way make them more sensitive to the social and environmental problems in their vicinity.

As you start on your quest to gain executive support, do research and observe all the executives. Some executives have more influence than others, and some are more likely to support new initiatives than others. Our friends at Greenbiz featured a great article in 2018 titled 5 ways to engage your senior leadership on sustainability strategy by Beth Richmond at CSR. The article highlights 5 key strategies:

- Change the rules of the game

- Look forward, not backward

- Use numbers wisely

- Create sophisticated communications strategies

- Do not go it alone

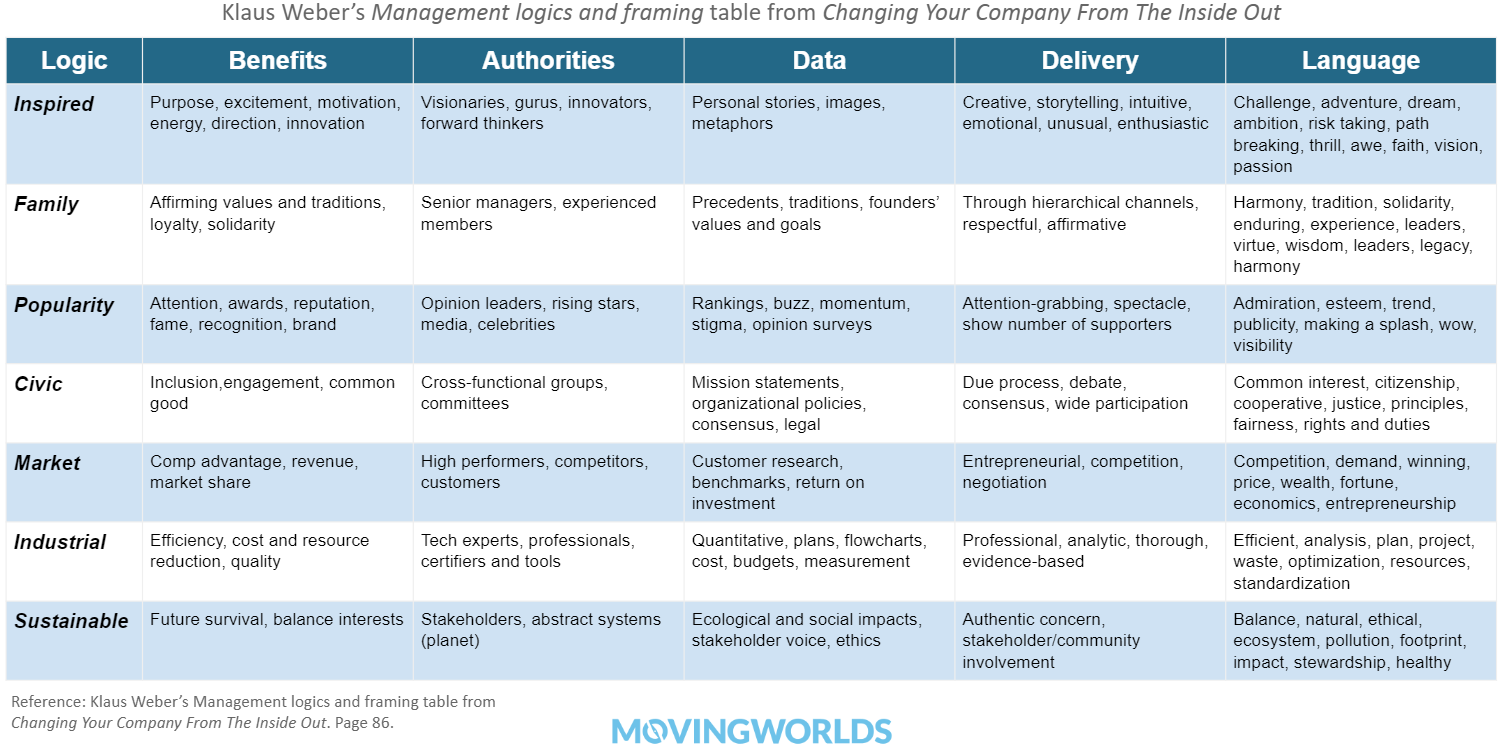

To gain the right level of support, you’ll not only need to build a compelling business case (here's some tips to do this), but also show why doing so aligns with their idealogies. Your goal is to appeal in such a way that will resonate with the logic model employed by your executives. So how do you navigate decisions if merely building the business case is not enough? We recommend using the logic framework outlined by Klaus Weber in the book, Changing Your Company From the Inside Out (pg. 86).

Keep in mind that you will get a lot of questions challenging your ideas and be pushed to answer the "so what" question. It’s not uncommon that first attempts to gain executive sponsorship are denied or delayed. Don’t lose hope. Instead, revisit the case and logic model, and try again from a different angle and/or in partnership with another influencer.

And here's a tip from multiple CSR leaders that we spoke with in the creation of this guide: show industry date and use peer pressure. You can "benchmark" your executives by showing what close competitors (whether for customers or employees) are doing, as well as trends in the industry. We use a scorecard to help companies understand where they are relative to companies they compete against. In many cases, we've seen social impact leaders use news stories and quotes from speaking engagements.

Chapter 13: Empowering (and Aligning) Employees

As social good initiatives at your company grow, employees will be empowered to participate and bring their own passion projects. Both should be encouraged, but a little structure can help. As your program grows, you’ll want to communicate it in a way that ensures the following can be easily understood by employees participating:

- Why is your company investing in this effort, even if just a pilot?

- What is your company hoping to get out of the program?

- What can your fellow colleagues/ other employees expect to get out of the program?

- Who is your target beneficiary audience, and why?

As importantly, managers must also know these, and you’ll need to take a bottom-up and top-down approach to communicate these important details. Common tactics to do this include:

- An email from sponsoring executives to key stakeholders and participants

- Published documentation via an internal blog, website, and/or printouts

- Additional training (i.e. recording webinar, video series, online LMS)

- Internal, online community group and/or listserve on this topic

- Presentations during all-hands meetings

Chapter 14: Going Public Within the Company and Beyond

Go to the people. Live with them. Learn from them. Love them. Start with what they know. Build with what they have. But with the best leaders, when the work is done, the task accomplished, the people will say 'We have done this ourselves.’ - Lao Tzu

Remember that engaging in CSR for the wrong reasons can have a negative consequence. As such, if your programs are really designed the right away, you won’t need to invest in your own storytelling, as your partners and employees will do that for you. Aand you want this to happen: according to Edeleman’s Trust Barometer mentioned in Chapter 1, people trust other “people like me” and nonprofits more than they trust corporations.

With the proper program design, there are ways to make sure you collect the right assets (like photos, images, quotes, and surveys), and to set the stage to encourage your program participants to share their stories on their own. Consider how you want to get the word out about your program — it could be a press release to media, or it could be a blog or social media post from a company channel. You’ll want to brainstorm this with someone in your marketing, PR, corporate affairs, internal communications, HR, and/or communications team to come up with the best ideas. By thinking about this in advance, you'll make sure to capture the right assets. You'll then want to work with someone in your PR, communications, and/or legal teams to develop a few key tools:

- A PR & Media authorization form for employees and beneficiaries. Get participants from all stakeholder audiences to sign this so you can use media and quotes that result of your first pilot.

- Create an educational guide and/or short online course for your employees that shares tips on how to best share their stories in impactful, empowering ways (often times, in an attempt to share their stories and experiences with others, people will unwittingly use words or photos the erode dignity and propagate stereotypes).

- Provide a reflection worksheet to participants so that they can journal goals, intentions, and emotions. During their participation, they can catalog events, a. And after, it should guide them through a reflection process to cement learning.

- Engage managers and/or cohort-based accountability. It’s easy for employees to get lost in the ‘tyranny of now’, and they will likely forget to do things like submit reflections, complete surveys, and share stories and photos.

- Tailor messages for your key audiences. Help your participants share content that will be relevant to the different audience groups.

Chapter 15: Continue to Scale

What do you do after your program is in place and growing? It’s time to help others identify more opportunities within their own roles and launch their own initiatives. This can happen in any number of ways, but usually requires that the systemic issues are addressed within your company.

In our research, we find that the most successful CSR programs are NOT initiated by CSR teams or Social Impact leaders. Rather, CSR becomes a platform for all business units across the company to integrate social impact into their own business.

The most effective way to scale CSR is to integrate it into the core aspects of your business: your processes, your people, and your profit-making activities. McKinsey has a great guide to help you lead change within an organization: The four building blocks of change.

Appendix and Resources

CSR Associations:

- Shared Value Initiative

- Benefit Corporation

- Social Value International

- Association of Corporate Citizenship Professionals (ACCP) (and make sure to check out its guide of the profession here)

- Business for Social Responsibility (BSR)

CSR Conferences:

- ACCP’s Annual Meeting

- U.S. Chamber of Commerce Citizenship Center Conference

- BSR Conference

- GreenBiz

- Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship

- Ethical Corporation’s Responsible Business Summit